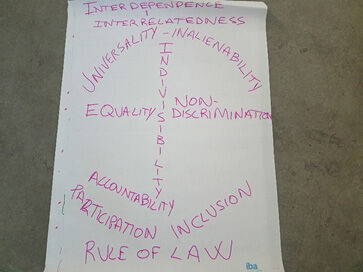

Illustration of the conceptual issues of the human rights-based approach (Photo: Christoph Engeli / MMS)

“The idea that ‘no goal should be met unless it is met for everyone‘ is well established in the rhetoric around the new SDGs“1. The Core Responsibility “Leave no one behind “2 (see Agenda for Humanity), echoes this commitment “to transform the lives of those most at risk of being left behind“ in humanitarian interventions by “reaching everyone and empowering all women, men, girls and boys to be agents of positive transformation“. All human rights carry corresponding obligations that must be translated into concrete duties to guarantee these rights. However, what this means in practical and programmatic terms seems not to be completely clear for many humanitarian and development workers, communities and governments, who still pose many questions around what rights-based programming does look like, and which the roles, responsibilities and opportunities of both right-holders and duty-bearers are.

There are number of conceptual issues guiding the development of a human rights-based approach in state fragility

If human rights and their principles may be seen as the primary basis of states – and therefore for state-building – or even as a “conceptual, normative and operational framework for engaging complex challenges of institutional development”, an initial challenge arises from the fact that the debate about rights-based state-building has tended to focus “on what states should be doing and (…) determine how donors ensure they get there“.3 In principle states assume obligations and duties under international law to respect, to protect and to fulfil human rights. Beyond that, the link between human rights and international humanitarian/development programming remains unclear for many, and the role of communities as actors of change, or the responsibilities of international actors as duty-bearers are often not directly tackled.

Who are we talking about?

As an example, when discussing about rights-holders, questions often turn around who are “communities”? Who are “the most at risk of being left behind“? Can these groups be “listed” in fixed categories for prioritization/targeting purposes? Which is the role (and opportunities) of communities and affected populations to be actors of change, so to avoid a “top-down” approach? Civil society, local organizations, community workers and the community at large play a crucial role in contributing to reach out to/towards people at risk of being left behind (or factually left behind) and support the gap in fragile states where governmental or international aid professionals are scarce; they could still find more opportunities to participate in positive transformation also in humanitarian action, but the how to of participatory and community approaches seems like a secret and inaccessible formula for many. For example, following the „Participation ladder“ referenced in the Protection Mainstreaming Training Package4 that classifies types of participation as passive; information transfer; consultation; material motivation; functional; interactive and ownership.

Conclusion from the working group "Leaving no one behind: How can we respect and fulfil human rights principles in fragile contexts?" at the MMS Symposium 2016 (Photo: Christoph Engeli / MMS)

Become international actors duty-bearers in fragile contexts?

On the other hand, international actors often see themselves in the role of determining needs of affected populations and means for addressing them,3 supporting states as duty-bearers and communities as rights-holders, but rarely see themselves as duty-bearers in terms of promotion and protection of human rights, including that of participation: have humanitarian/development actors also responsibilities as duty-bearers in extreme humanitarian or fragile contexts where the environment is marked by instability, the public structures are weak or quick to collapse and the rule of law is lacking?

Finally, when discussing the how to of rights-based programming, some of the following questions pop-up: are global frameworks, such as the SDGs, self-explanatory to articulate human rights principles and humanitarian / development programming? Is there a need for other initiatives to “translate” human rights into programmatic actions at smaller scales, to Make the Right Real or BRIDGE human rights, SDGs and international development? Are initiatives that link human rights and humanitarian action, such as Protection Mainstreaming, the Youth Compact (pdf), the Charter on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action or the Call to Action on Protection from Gender-based Violence in Emergencies (pdf) known, understood and a buy-in among humanitarian actors? Are all these initiatives known also by right holders and other duty-bearers, such as governments, and applicable to all fragile contexts? What is, in definitive, needed to strengthen, implement and monitor initiatives developed to ensure that human rights principles are respected and fulfilled in fragile contexts?

Conclusion

There are complex relationships between rights and violent conflict, and between rights and fragile states. Although the infringement of human rights is most common in conflict situations and fragile states, there remains a debate as to what extent rights-based approaches provide useful tools in these contexts for guiding policy formulation and design of interventions by the international community. A rights-based approach is implicit in the set of principles established for guiding the protection of civilians and a rights-based approach is often claimed to underlie the provision of humanitarian assistance to meet basic needs for the population in conflict situations.

References:

1) «Leaving no one behind. How the SDGs can bring real change». Briefing Paper. ODI, Development Progress

2) Core Responsibilities: the foundation of the World Humanitarian Summit : http://www.unocha.org/top-stories/all-stories/core-responsibilities-foundation-world-humanitarian-summit

3) Evans, D. Human Rights and State Fragility: Conceptual Foundations and Strategic Directions for State-Building“. Journal of Human Rights Practice Vol 1 | Number 2 | 2009 | pp. 181–207 DOI:10.1093/jhuman/hup007: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241924351_Human_Rights_and_State_Fragility_Conceptual_Foundations_and_Strategic_Directions_for_State-Building

4) Protection Mainstreaming Training Package: http://www.globalprotectioncluster.org/_assets/files/aors/protection_mainstreaming/PM_training/1_GPC_Protection_Mainstreaming_Training_Package_FULL_November_2014.pdf

Make the Right Real: campaign, for example, aims to accelerate the ratification and the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in Asia-Pacific: http://www.maketherightreal.net/

BRIDGE is an intensive programme that aims at supporting DPO activists to develop an inclusive (all persons with disabilities) and comprehensive (all human rights) CRPD perspective on development, including the post-2015 agenda and sustainable development goals (SDGs) to reinforce their advocacy for inclusion and realization of rights of persions with disabilities. BRIDGE is a joint initiative by the International Disability Alliance (IDA) and the International Disability and Development Consortium (IDDC), also joined and supported by the Disability Rights Fund (DRF)

Protection Mainstreaming, Protection mainstreaming is the process of incorporating protection principles and promoting meaningful access, safety and dignity in humanitarian aid. http://www.globalprotectioncluster.org/en/areas-of-responsibility/protection-mainstreaming.html

The Youth Compact lays out six actions that signatories pledge to take to ensure that the priorities, needs and rights of crises-affected youth are addressed, and that young people are informed, consulted and meaningfully engagted in all states of humanitarian action. http://www.un.org/youthenvoy/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/CompactforYoungPeopleinHumanitarianAction-FINAL-EDITED-VERSION1.pdf

The Call to Action on Protection from Gender-based Violence in Emergencies aims for every humanitarian effort to include mechanisms to mitigate SGBV risks, and to provide safe and comprehensive services for those affected by SGBV. http://www.unhcr.org/ngo-consultations/ngo-consultations-2016/WHS-commitments-follow-up.pdf

The Charter on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action propose 5 key principles to make humanitarian action more inclusive of persons with disabilities, by lifting barriers persons with disabilities are facing in accessing relief, protection and recovery support and ensuring their participation in the development, planning and implementation humanitarian programmes. http://humanitariandisabilitycharter.org/