The recognition that sport and play are supportive and complementary tools to reaching development and peace objectives has grown enormously over the last ten years (Dudfield 2014:2). Sport and play have innately inclusive and interactive qualities that have the power to impact positive social change in a fun and engaging way. Well-designed sport and play-based learning programs can act as powerful platforms for communication, education, and social mobilization.

Research shows that sport and play are effective tools for increasing knowledge on how to prevent communicable and non-communicable diseases (SPD IWG 2008). It is important for youth to gain knowledge on vital health issues relating to SRHR but also the confidence to make healthy choices so that they can protect themselves from diseases, and reduce high-risk behaviours. Learning through sport and play allows children and youth to actively engage with, and enjoy the learning process while enhancing social connectedness between students and teachers. Fostering learning in this way can help break down barriers to discussing sensitive issues and create an environment more conducive to open communication.

Furthermore, sport and play are effective vehicles for teaching children and youth important life skills such as team-building, communication, decision-making and problem solving, while encouraging the acquisition of positive attitudes and values. Life skills are critical in supporting decision making for children and youth and their development through each stage of life. For adolescents in particular, sport and play can increase self-esteem and facilitate identity formation through relationship-building and enhanced access to leadership opportunities (Koss 2011: 2).

Right to Play's Methodology and Pedagogical Resources Related to SRHR Issues

Right To Play’s methodology, entitled “Reflect – Connect – Apply” (see Box: Experiential Learning Cycle) is based on the work of educationalists such as Freire, Brown, Piaget, Bransford and others, all of whom cumulatively support the concept of an educational process that is active, relevant, reflective, collaborative and applied. The activities are designed for a range of different ages and development stages, and are focused on a variety of key learnings. These key learning outcomes linked to different topics are then transferred to children and youth through various sport and play activities. These games are housed in pedagogical resources.

Experiential Learning Cycle

In each sport and play session, key messages are introduced and reinforced in opening and closing discussions. During the sessions, activities and games enable participants to experience situations and feelings similar to those they encounter in real life. At the end of each session, the Reflect-Connect-Apply strategy guides participants through a three-step processing of their experiences:

Reflect: What did I just experience?

Connect: How does this experience relate to earlier ones? How does it connect to what I already know, believe or feel? Does it reinforce or expand my view?

Apply: How can I use what I have learned from this experience? How can I use it in similar situations? How can I use this learning to benefit myself, my community?

(David A. Kolb (1984): Experiential Learning Theory)

My Life, My Plan

My Life, My Planis Right To Play’s key SRHR resource; it supports Teachers, Coaches, and Community Volunteers in implementing play-based learning activities for children and youth on SRHR knowledge and attitudes. It specifically looks at the main challenges that children and adolescents face regarding their SRHR, and helps them to prevent, address and make positive decisions in relation to these challenges. Key topics include:

- Adolescent Development: Providing children and youth with information about the physical, emotional and behavioural changes they can expect as they go through adolescence and ensure that they make well informed life decisions.

- Communication: Explaining what healthy communication is and why it is important to SRHR; understanding the importance of healthy communication between peers, parents and partners.

- Relationship: Explaining which behaviours can improve or damage a relationship; talking about what qualities define friendship and romantic relationships, and how to make effective decisions and apply this to sexual decisions; practicing resisting pressure. Sexuality: Developing youth’s awareness and providing objective and accurate information regarding sex and sexuality; dispelling myths and misinformation; developing awareness of sexual and gender-based violence; empowering youth to access referral services to report abuse and seek social support.

- Planning My Future: Using decision making strategies that can be applied to difficult decisions related to SRHR; understanding various methods of contraception and how to correctly use them; understanding how to prevent and deal with teenage pregnancies, discussing concepts of early marriage.

For all the different topics and learning outcomes, Right To Play has compiled diverse games that are based on an experiential approach to learning.

In Practice - Enabling Change for Youth and Their Environment

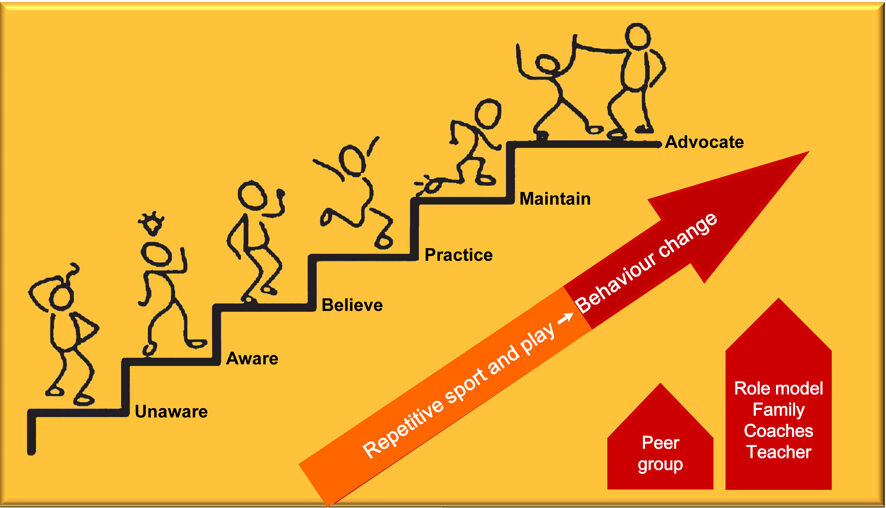

To ensure sustainable behavior change in youth, it is necessary to involve them, as well as their circles of influence, actively. This includes community, government and society in general. Engaging with these spheres of influence creates an environment that provides the opportunity for children and youth to behave differently. At the same time, behavior changes in the child also shape the spheres of influence. This creates a two way dynamic process of change, where the individual impacts the collective change process and brings about a normative shift in society.

By participating in regular weekly sport and play activities in schools and at a community level, youth not only gain knowledge about SRHR but they learn essential life skills. For example, games teach youth about correct condom use and educate both genders on their health rights and responsibilities. Coaches use the experiential learning approach - Reflect – Connect – Apply- to discuss the risks of HIV with youth, teach them healthy behavior, identify misinformation, and reinforce correct prevention knowledge. At the same time, children and youth play games like “No Means No” and “Decision Time” that teach them critical life skills such as confidence and decision-making. Enhancing these critical life skills is key as they are the foundation to achieving improved attitudes and behavior change.

By participating in Health and/or Child Protection clubs, youth have the opportunity to actively lead initiatives (e.g. interschool debates, etc.) to sensitize their peers and the community on SRHR. Through their active participation in those clubs, they learn how to confidently lead debates, and enhance their self-esteem and sense of agency.

In 2014, a forum led by children and youth clubs from Bugesera, Rwanda, was held to address issues of SRHR and HIV. It was structured as an opportunity for youth, parents, and other community members to improve communication surrounding these topics. The event also included some capacity building sessions on actions different stakeholders can take in order promote the healthy development of children and youth. Beyond the important messages provided in the forum, it was seen as a great success because of the leadership demonstrated by the children and youth club organizers. These types of initiatives not only build young peoples’ skills but also shift adult perceptions of what they are capable of, allowing them to become greater agents of change in communities.

Youth live in a supportive environment

Right To Play’s approach to health promotion and disease prevention also includes activities to strengthen local and national partnerships and to stimulate the involvement of parents, caregivers, community leaders and governments.

a. Community

Education on SRHR is not only provided to children and youth but also to their Important Others – i.e. teachers and coaches, family, parents, community members and health workers. Sensitization, awareness and capacity building initiatives bring the community together to reflect and work on change – having influential leaders in the community (e.g. religious leaders, teachers, local authorities) reinforcing the messages - demonstrating local, cultural and social acceptance of the messaging.

Important Others: Teachers and Coaches

The training on the My Life, My Plan resource enhances Teachers’ and Coaches’ understanding of the importance of sexual and reproductive health for children and youth in their communities and equips them with the skills and information required to discuss and teach it. Well trained teachers and coaches are able to create safe and supportive environments, and foster the development of essential life skills and healthy attitudes. They also serve as role models of healthy behavior and as trusted adult for youth to talk to about their SRHR. Teachers and Coaches are also an important part of community referral systems that can guide youth and link them with service providers and authorities when needed.

Volunteer Coaches and teachers we are collaborating with in schools and community centers expressed their difficulties to talk openly about sexual and reproductive health with the youth they interact with. In many countries, Sexual Education is only partially covered in the biology or natural sciences class, and teachers lack knowledge and tools, but also confidence, to be able to implement this part of their program successfully and overcome the taboos.

Important Others: local leaders and parents

Right To Play also encourages a community-wide response to health promotion by holding sensitization events that build and reinforce positive health knowledge and behaviours among key influencers in the community. Parents and the broader community are engaged through discussions within parent-teacher associations, as well as Play Days and sports tournaments, on topics such as early marriage, child protection, teenage pregnancy and HIV/AIDS. Special days (like Population Day, etc.) are also used to gather people around a sport activity and diffuse important messages.

As a result they become positive role models within their communities to further promote healthy messages and positive practices, and at the same time improve the understanding of youth needs and the way they talk about SRH.

Important Others: health workers

Access to reproductive health services is an important element of any SRHR program. Right To Play’s expertise is not to provide health services, so we partner with stakeholders that can adequately refer youth to other organizations that provide resources such as voluntary counselling and testing (VCT), antiretroviral (ARV) medications, condoms, sanitary pads, and other health services.

Furthermore, we involve health workers in the training of teachers and coaches, play days and community mobilization events, either for them to expand or to share their knowledge and technical experience.

b. Government – local authorities and relevant ministries

Supporting the strengthening of local systems is an important component of a SRH intervention. We work collaboratively with partners, stakeholders, and government at community, national and regional levels to help strengthen the quality of health education and services. The improvement of the quality of health education, as well as the inclusion of a youth friendly and integrated approach to SRH into local and national policies are crucial to ensure the sustainability of the actions.

In Rwanda Right To Play is a strategic partner of the Ministry of Education working to support the revision of their primary education curriculum. Through this process Right To Play is providing technical assistance, where our methodology will be integrated to improve education quality (child centered and play-based approach). We are using this unique position to advocate for the integration of SRH education in the formal education curriculum, including Right To Play play-based methodology.

In Tanzania, Right To Play, along with other organisations of Child Protection networks, is part of the movement advocating to change the national law on the age of marriage. Indeed, while the current legal age of marriage for boys is 18, girls are legally eligible to marry at 15. Either sex can marry at 14 with court approval, this contributing to early marriage (Children’s Dignity Forum 2013).

c. Society

All above mentioned actions, together with targeted and positive messaging through the media and athlete ambassadors’ examples, contribute to change in society as a whole: a change in perceptions, overcoming stereotypes and harmful cultural beliefs.

Lessons Learnt to Enhancing SRHR

- The importance of multilevel and multisectoral approach: Working on providing better access to and quality of health services for youth is essential but not enough on its own. Working to achieve education outcomes, gender equality and guarantee child protection is vital to address SRHR related issues. For example, enhancing quality education, remaining in school (especially for girls), having access to higher level of education and tackling gender-based violence are crucial aspects influencing directly youth SRHR.

- Play and sport prove to be a successful way to overcome resistance and taboos.

- Life skills development is an added value to SRH interventions with youth. It allows them to feel confident and well equipped to take healthy decisions, have their decisions respected by others and seek support of people of trust and professionals if required.

- Right To Play’s approach is complementary to other stakeholders’ efforts. Therefore, building strong partnerships with health centers, community based organisations, local and international NGOs and the government is key to leverage the effectiveness of sport and play as a tool to improve SRHR situation.

About Right To Play

Right To Play is a global organization using the transformative power of sport and play to create behaviour and social change. Right To Play trains community coaches and teachers to implement programmes which are designed to build essential life skills, enhance education quality, transform health practices and build peaceful communities. Currently, Right To Play works in more than 20 countries reaching one million children and youth in regular weekly activities with the support of more than 16,400 coaches.

www.righttoplay.ch

References

Children’s Dignity Forum (2013): Preventing and Eliminating Child, Early and Forced Marriage in Tanzania, December 2013 (http://www.ohchr.org)

Dudfield, Oliver (2014): Sport for Development and Peace: Opportunities, Challenges, and the Commonwealth’s Response, in: Strengthening Sport for Development and Peace: National Policies and Strategies. The Commonwealth.

Kolb, David A. (1984): Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Koss, Johann (2011): Building a Strong Foundation: effective youth development through sport and play, in: Commonwealth Ministers Reference Book.

Sport for Development and Peace International Working Group (2008): Harnessing the Power of Sport for Development and Peace: Recommendations to Governments.